The Tournament System: What is the tournament system? How are chicken farmers paid?

WHAT IS THE “TOURNAMENT SYSTEM?”

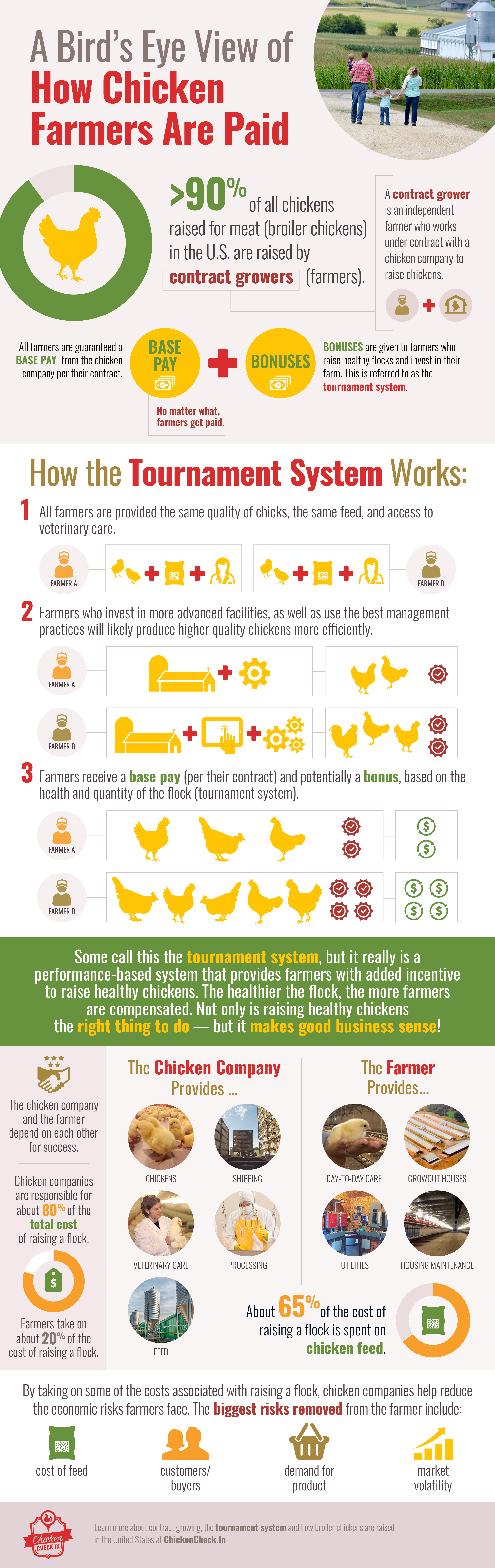

Chicken farmers are paid under a contract with a chicken company based on their performance in raising the healthiest chickens. This performance-based or incentive structure is sometimes referred to as the “tournament system.”

Farmers are paid according to both the quality and quantity of their flock, as well as how efficiently the chickens are raised. All of these aspects are clearly laid out in the contract that a farmer voluntarily signs prior to raising chickens. The phrase “tournament system” is really a bit of a misnomer. In reality, all contract chicken farmers get paid a minimum base rate for the chickens they raise, with the potential for a slightly higher rate for the farmers who are the most successful at raising birds. It’s like a set payment with a performance bonus. When we talk about how the tournament system operates, we’re usually talking about the factors that play into the performance-based aspect of the payment structure.

This structure—based on the most fundamental elements of any business atmosphere—is the best way to ensure that chicken farmers are rewarded for producing quality chickens in an environmentally sustainable way. It also ensures that the welfare of the birds is the farmers’ top priority.

While all contract farmers are provided the same quality of chicks, the same feed, and access to veterinary care, farmers who invest in more advanced facilities and farmers who put the most effort into the best management practices will likely produce higher quality chickens more efficiently. And they get rewarded for their success.

HOW EXACTLY DOES THE TOURNAMENT SYSTEM WORK?

Here are the key elements to how the tournament system works:

- Farmers are delivered chicks on the day that they are hatched, to be raised in the houses provided by the contract farmer. Chicks sourced from the same hatchery get delivered to many different contract farmers.

- The chickens, feed, veterinarians, animal welfare experts, transportation and marketing are provided by the company, and farmers provide the housing, maintenance and day-to-day care of the flocks. (About 65% of the cost of raising a chicken is the feed.)

- Farmers and companies agree on a predetermined per pound price of weight gain built around an average, which guarantees the farmer a certain rate for all chickens that meet certain standards when the birds reach market age.

- Farmers are paid based on the weight gained by the flock, meaning that farmers with greater skills and better management, combined with advancements on the farm, will earn a little more.

- However, all farmers are paid a base, prearranged compensation, and all farmers are held to standards of animal welfare that ensure sound animal husbandry. Abuse of any kind is not tolerated, and if found, can lead to the termination of a farmer’s contract.

Here’s another way to think about how the tournament system works with a classroom analogy:

Three students are taking the same class. Each student is given the same study materials and resources for the class.

- Student A attends every class, studies throughout the semester, goes to study hall and office hours, actively participates in class and completes all homework assignments.

- Student B attends most classes, studies here and there, attends study hall a few times, does not attend office hours, sometimes participates in class and completes all homework assignments.

- Student C has missed several classes, pays less attention in class, only studies right before exams, doesn’t attend study hall and does not ask questions or engage with the professor.

Which student deserves to get an A in the class? Student A, of course. Student A puts in the most effort and invests the most time studying.

Even though each student has the same tools and resources available to achieve an A in the class, their performance and investment in studying varies. This explains why each student will get a grade that is commensurate with their effort and investment in the class.

The tournament system works similarly for farmers. Farmers who invest in more advanced facilities and who put in the most effort in best management practices will likely produce higher quality chickens more efficiently; these farmers will, in turn, be compensated at a higher rate.

DOES THE TOURNAMENT SYSTEM CREATE TOO MUCH COMPETITION? DOES THE TOURNAMENT SYSTEM PIT FARMERS AGAINST OTHER FARMERS?

Under the current performance-based incentive structure, growers typically are compensated based on the quality of feed efficiency, low condemnations and the quantity of liveweight pounds delivered to the processing plant. This is not really a “tournament” — it is a performance-based structure that aligns with fundamental free market principles to encourage efficiency, improve performance and incentivize farmers to use the best welfare practices for the birds.

Thus, two farmers who produce the same “type and kind” of poultry might receive different compensation depending on their productivity and efficiency. Farmers with more advanced facilities/processes and management skills will likely produce poultry more efficiently and of a higher quality. These growers are rewarded accordingly through greater compensation.

The current system has worked well for decades since the vertically integrated structure of the broiler industry was adopted. Tens of thousands of families on small farms who otherwise would have had to get out of agriculture altogether have been able to not just survive, but thrive. Most companies have waiting lists of people who want to become farmers and lists of existing farmers who want to add capacity by building more growout houses. These farmers understand raising chickens under contract can be rewarding while risks are more manageable.

These risks are not insignificant. About 65% of the cost of raising a chicken is feed, which is paid by the company. Chicken farmers do not have to worry about the price of corn and soybeans, or the risk of a flood, freeze or draught that could make feed costs skyrocket, as they have multiple times over the past decade. They don’t have to manage their own chick production or breeder flocks, or worry about developing optimized feed, obtaining veterinary care, or even finding someone to sell their chickens to. Chicken farming is hard work and not a 9-5 job; it is a way of life. But the risks are distributed among the parties best positioned to shoulder them, and that is why this partnership has worked so long for both processors and farmers.

Chicken companies remove approximately 97% of the economic risk from growers, compared to independent growers who bear all of that risk on their own.

Knoeber, C.R. and W.N. Thurman (1995), “’Don’t Count Your Chickens…’: Risk and Risk Shifting in the Broiler Industry”, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 77(3), p. 486-496

If all poultry growers of the same bird type must receive the same base pay, as some argue, farmers who made greater investments in their facilities and processes might not be compensated accordingly, ensuring that the best and most innovative growers are not rewarded for their efforts. Progressive growers who invested more of their time and resources in their housing or growers with new construction built at a greater cost than older houses would nonetheless get the same base pay as growers with older housing and growers who chose to devote their time and effort elsewhere.

DO COMPANIES PROVIDE INFERIOR CHICKENS OR BAD FEED TO FARMERS THEY WANT TO “RETALIATE” AGAINST FOR SOME REASON?

No, chicken companies do not provide inferior chicken or bad feed to farmers.

First, it would be impossible to sort out chicks that are “bad” or feed that is “bad” from the millions of chicks that hatched each week, or the millions of tons of feed that is blended. Second, it makes no economic sense for a company to do anything to harm the success of the farmer it contracts with. It would directly affect the bottom line because the ultimate success of the company depends on the farmer.

IS THERE ANY GOVERNMENT OVERSIGHT OF THESE CONTRACT GROWER CONTRACTS? IS THE TOURNAMENT SYSTEM REGULATED?

Yes, the chicken company-farmer relationships are extensively regulated by federal law. Livestock and poultry procurement and marketing practices are regulated by the Packers and Stockyards Program within U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS), which administers and enforces the Packers and Stockyards Act to protect farmers, ranchers and consumers.